Stuart Fleischer

Throughout history, places of religious worship have served as the centerpieces of ancient cities. The temples, pyramids, ziggurats, and the other buildings and structures of religious worship that are in this exhibit were all the focuses of their respective cities. These buildings also each convey a narrative, or a story. Many religious institutions of the ancient world constructed the buildings to send out a narrative to the citizens and anybody else who witnessed them. Although the messages that the religious institution were trying to send are usually different from place to place based on religious beliefs and social customs and norms, the reason for telling the public the narratives was mostly the same, to reflect the ideals and beliefs of the religious institution in which the person with the most power in society was associated with. Some of these structures also reflected values that the society held dear through their design. By looking at works of architecture of the ancient world from societies of the Near and Middle East, Egypt, the Mediterranean region, and Rome, this exhibit will demonstrate how each culture’s religious institution was telling a narrative to its city’s people and explore the effects that the narrative might have had on the lives of the people who came into contact with the structure. This exhibit will also look at how some of the pieces of artwork use illusion and deceit to help create narratives and then discuss some repercussions that this might have had. Included in the exhibit are the Great Ziggurat at Ur, the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari, the Parthenon of Greece, the Great Altar from Pergamon and the Pantheon in Rome. Although they are from different parts of the world and of different time periods, they each share the fact that they each use narrative to try to convey a message to the people that saw them.

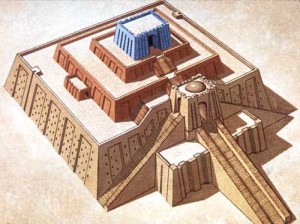

The first structure that will be looked at in this exhibit is the Great Ziggurat of Ur, located in modern day Iraq. It has also been referred to as the Nanna Ziggurat. A ziggurat is a giant edifice with multiple platforms that rise high into the sky, creating the illusion of it ascending into the heavens. This ziggurat in particular stands about 100 feet tall, which is actually a rough estimate because of the damage to the structure over the centuries, and 210 by 150 feet in the length and width respectively. Like many other ziggurats of the time, it was built in synchronization with the orientation of the cardinal directions; the front stair case, one of the three massive stair cases that lead to the upper platforms is pointed towards the north. The construction of the ziggurat was ordered by Ur’s king Ur-Nammu. It was first built around 2100 BCE, but has had a lot of reconstruction done over the centuries since to ensure its longevity. It looks somewhat similar to a step pyramid, but the ziggurat also doubled as a temple complex. At the top was a small temple dedicated to city’s chief deity Nanna, the god of the moon, although this temple has been destroyed by time, neglect, and warfare. The foundation of the ziggurat is mostly made of dried mud brick, literally dried blocks of mud. Although the temple no longer exists, remains of blue glazed brick have been found in excavations, which have been speculated by some archaeologists to be decorations of the temple (German). The ziggurat was the focal point of Ur, standing at the center of the city. Surrounding the ziggurat were the houses of the citizens, smaller temples dedicated to other deities, two harbors that connected to the Euphrates River, businesses, and even a royal cemetery, which was dubbed by British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley “The Great Death Pit.” Ur’s system of government was theocratic. The rulers of the city were the kings and high priests. This ruling class was depicted in various pieces of ancient art as being able to communicate with the gods. An example of this is in the Stele of Ur-Nammu, where we see who art historians believe to be the god Nanna sitting in his throne conversing with the king Ur-Nammu. The Stele of Ur-Nammu may be the depiction of a religious ceremony meant to honor the god. Only the priests and king could participate; the common person was not allowed to ascend the ziggurat and partake in the ceremonies that took place at the top. From ground level, it was hard for the common person to see what was going on at the top of the ziggurat during the ceremony. The people in power, by keeping the people ignorant, had created the narrative that the ziggurat was a place where the supernatural and natural worlds met at the top of the mountain and that the king was basically a demi-god that was negotiating with Nanna to keep the city prosperous. By using the powers of ignorance and deceit, the king was able to keep the common people under control and because they believed the king to be a god, he was able to maintain an absolute divine right style of ruling with relative ease. This deceptive narrative might have had several effects on the common person. Out of fear of punishment from their god-king, the people of Ur were unlikely to disobey any laws that were created by him. The Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest code of law known to man, created by Ur-Nammu, outlined what the laws of Ur were and the penalties associated with breaking them. Ur-Nammu’s laws were relatively peaceful when compared to other ancient codes of law like the Code of Hammurabi, but having the power to create a law system with unquestioned authority can lead to a very malignant set of laws which could set in motion the persecution of certain groups of people, similar to what the Nazis did to the Jews during the Holocaust. Another possible effect of the deceitful narrative communicated by the ruling class is the idea that the king could basically tell the people whatever he wanted and say that the god orders them to do it. This could have led to huge buildings, like more ziggurats, being able to be built at great speeds, but it could have also lead to the slavery of the people who were forced to build them. When deception is used to produce ignorance in the people, it creates a narrative that puts the ruling class at the top of the power pyramid, in this case quite literally.

The next piece of architecture that will be looked at in this exhibit is the Ishtar Gate of the ancient city of Babylon, which is also located in modern day Iraq. Only reconstructions of the gate exist today. It served as one of the main entry ways into the city proper. It was constructed around 575 BCE under the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II, who was the king of Babylon at the time. Under Nebuchadnezzar II’s rule, Babylon was transformed into a city of prosperity and beauty through his generous funding towards the building and restoring of architecture and urban development. He is responsible for the building of not only the Ishtar Gate but also the walls surrounding the city and the ziggurat in the center of the city, Etemenanki, dedicated to the patron deity of the city, Marduk. It is even speculated that he was also responsible for the legendary, wonder of the ancient world, Hanging Gardens, although there is no proof that the gardens ever actually existed (Garcia). The Ishtar gate stood over 38 feet tall and is constructed of burnt brick (Encyclopedia Britannica). The gate is a beautiful blue color, signature to the stone lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli is a valuable stone because it is mainly only found in certain mountainous regions of Afghanistan which meant that Babylon had to trade to in order to get it. While a majority of the gate is the deep blue color of the stone, there also are relief mosaics depicting three animals: the lion, the auroch, and the dragon. These mosaics stick out from the wall slightly and cast a shadow. The gate is dedicated to the goddess of the same name, Ishtar. She was the goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex. The lion was symbolic of the goddess and represented her warlike ways. The auroch, which is an extinct ancestor to modern day cattle, was representative of the god Adad, the god of storms. The dragon was representative of Babylon’s patron deity, Marduk. If one were to walk through the Ishtar Gate they would then find themselves at the Processional Way, which was used during the New Year’s festival and also led to Etemenank (MET Museum). This passageway is also covered in lapis lazuli and again features relief sculptures, but this area only features Ishtar’s lions. An optical illusion takes place as you walk along the procession; due to the shadows cast by the relief sculptures it appears as if the lions are walking along side you. This might have given those walking on the path a sense of protection from the goddess. Another interpretation is that the goddess is watching carefully, ready to pounce on those who do not honor her. The Ishtar Gate is not just an entrance into the city and the Processional Way; it is also trying to tell a narrative. The gate tells the people what is important to their culture. The lapis lazuli shows how prosperous the city is because of its rarity and need to trade in order to obtain it. The animals, representative to the deities previously mentioned, tell the people of the city who the most important gods and goddess are. The illusion of the lions is evidence of the goddess walking amongst the people, which can be a sign of safety or danger depending on how it is interpreted. The illusion of the lions walking can also be an ancient version of GPS; the direction of the lion’s procession points you in the direction of Etemenanki, and since that is the ziggurat of the city’s patron deity it would have been a destination of interest for many in the city so having a lion guide you would probably be very helpful to the people of the city. The narrative that the Ishtar Gate is telling one that would help a person better understand and navigate the city of Babylon.

The third architectural marvel that will be looked at in this exhibit is the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. It is one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, the oldest and only one of the seven that is still intact, which is a testimony to how well the pyramid was constructed considering it was built around the year 2550 BCE during Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty. The pyramid’s construction was ordered by Pharaoh Khufu and because of this it is often also referred to as the Great Pyramid of Khufu. The pyramid stood 481 feet tall before erosion caused the building to get slightly shorter. Erosion or not, The Great Pyramid was the world’s tallest man made structure from the completion of its construction up until the year 1311 CE, over 3500 years. The Great Pyramid has four sides each approximately 755 feet in length. It is truly a massive edifice, one that is similar to the Great Ziggurat of Ur in that it would look like a mountain; the pyramid looks even more like a mountain because it has a point at the top opposed to the platform top of the ziggurat. The flat, desert landscape surrounding the Giza Plateau Complex makes this illusion even more noticeable. In ancient times, the sides were covered in a smooth, polished, white limestone, which would have probably reflected light that created an awe inspiring illusion of a shining mountain. Now, however, the polished limestone has been removed or eroded away and the pyramid’s yellow limestone is now exposed. The pyramid served as Pharaoh Khufu’s funerary tomb. The inside of the pyramid consisted of multiple different chambers, including the King’s and Queen’s Chambers (Encyclopedia Britannica). As was ancient Egyptian custom, Khufu was mummified and placed inside a sarcophagus along with all his earthly valuables that he could bring along with him into the afterlife. When he died it was said that he would ascend into after life and become a god himself. Despite being watched over by the mythical guardian the Sphinx, over the course of history the pyramid and its chambers have been infiltrated by tomb raiders, who stole everything they could, including the mummified remains of Khufu himself. Little is actually known of the methods used to build the great Pyramid. Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, recorded in his works that the pyramid took 20 years to complete and needed 100,000 men in order to complete it. His claims have been argued by modern day archaeologists, who suggest that only 20,000 people were needed to complete the pyramid’s construction (Fowler). The narrative that the pyramid was originally built to try to communicate was the story that Pharaoh Khufu wanted to tell, which was that he was going to ascend into heaven and become a god. The pyramid would not only serve as a portal in to the spirit world but would also be a symbol for his eternal afterlife because he made sure it was designed to survive for millenniums to come. When people saw his Great Pyramid, they would know that he was a great ruler and a deity because of his huge monument, regardless of how great of a ruler he actually was. With so little actually know about the life of Khufu other than the fact that he was the one who commissioned the pyramid, it is hard to know how effective of a pharaoh he actually was, but the narrative that the pyramid tells make it seem like he was a phenomenal ruler due to the massive size of his tomb. Present day, the pyramid is still telling this narrative by simply still existing; Khufu wanted to be immortal and his memory will still live on as long as the pyramid is still standing.

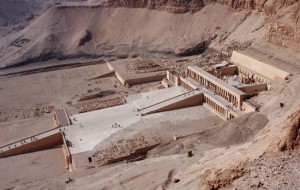

The fourth piece of architecture in the exhibit is the Temple of Hatshepsut, located in Deir el-Bahari, which is located near the Valley of Kings in Egypt. Hatshepsut was the daughter of the pharaoh Thutmose I. When her half-brother and husband Thutmose II passes away, she takes the throne and becomes the first female pharaoh of Egypt. Her stepson, Thutmose III, who would have taken the throne earlier had he not been only a child when his father died, was very bitter about having to wait to claim the throne for himself. It has been speculated by art historians that this bitterness led to him destroying almost all records of Hatshepsut which caused her to nearly be lost by history until her tomb was discovered in the 1920 (Sullivan). Part of the narrative being told by this building is being told through the vandalism and destruction done throughout the temple, which shows us how the lust of power can drive even family members to turn on each other. The temple of Hatshepsut was designed by Senmut, who was an architect, engineer, and the chancellor to the pharaoh. “Construction of the temple of Hatshepsut took fifteen years, between the 7th and the 22nd years of her reign. . . .The site chosen by Hatshepsut for her temple was the product of precise strategic calculations: it was situated not only in a valley considered sacred for over 500 years to the principal feminine goddess connected with the funeral world, but also on the axis of the temple of Amun of Karnak, and finally, it stood at a distance of only a few hundred meters in a straight line from the tomb that the queen had ordered excavated for herself in the Valley of the Kings on the other side of the mountain” (Siliotti 100). Hatshepsut did not coincidentally choose this valley and because of this, the location of the temple also tells a narrative. By choosing to put the temple in the valley dedicated to the goddess connected to the funerary world, Hatshepsut was guaranteeing herself a safe passage into the afterlife and ensuring her place among the gods when she dies. An interesting aspect of Hatshepsut’s depiction in sculpture is how she varies from sculpture to sculpture. When comparing two the sculptures “Seated figure of King Hatshepsut” and “Kneeling figure of King Hatshepsut” we see that although they originate from the same time period, the kneeling figure has a masculinized version of Hatshepsut, with a wider face than the sitting depiction of her. The kneeling figure also has a beard and more muscle tone. This differentiation in her depiction might also be telling its own narrative, one that might be reinforcing patriarchal norms. It is hard to be certain because of all of the destruction done by her step-son to her records, belongings, and the hieroglyphics and art that portrayed Hatshepsut. Because there are so few depictions of Hatshepsut in existence it is impossible to tell if Hatshepsut was depicted more frequently as a male or female. If she was depicted more as a male it might have been an attempt to hide the fact that she was a girl, maybe because the society was heavily patriarchal and could not stand to have a female as their pharaoh. On the other hand, however, if more of the depictions of Hatshepsut were of her in female form then perhaps the people were accepting of her rule regardless of her gender. It is unfortunate that Thutmose III destroyed all that he did because it could have given us more insight on how the ancient Egyptians viewed issues of gender.

The fifth work of architecture that will be examined in the exhibit is the Parthenon, located in Athens, Greece. The focal point of the Athenian Acropolis, this temple was dedicated in honor of the city’s patron deity, Athena. She was the goddess of wisdom, justice, and warfare, two principles held in high regards by the citizens of Athens. The temple was designed by architects Kallikrates and Iktinos and was completed in the year 432 BCE. The temple has a peristyle colonnade, with columns of the Doric order surrounding the temple’s pronaos, cella, and opithodomos. Inside the cella was a giant statue of the goddess Athena, which has since been destroyed or gone missing but reconstructions exist. Because of the small amount of light that could enter the cella through the colonnade, this statue would have appeared very surreal when the lights flickering on it, perhaps giving the illusion of it moving slightly. During ancient times, on the outside of the building one would see both the frieze and the pediment and the relief sculptures and metopes that were above the entrance way to the temple, and the sculptures would have actually been painted. This is contrary to what many are people used to seeing in museums today, which are usually plain, white marble sculptures, with any trace of paint fading off over the years. Many of these sculptures are no longer a part of temple and have been removed from the structure and are now in the British Museum as part of the controversial Elgin Marbles collection. Before a gun powder explosion caused destruction to the temple that damaged the sculptures beyond repair, if a person were to look at the eastern pediment they would see the mythological tale of the birth of Athena out of Zeus’ head. On the west side pediment one would see the myth about the contest between Athena and Poseidon to see who could offer the best gift in order to become the patron deity of the city (Silverman). Many art historians believe the images that appear on the friezes are depicting the procession of the Panathenaic festival, a festival held every four years to honor Athena (Jenkins). The relief sculptures that are on the Parthenon tell a narrative about how you should conduct yourself during the festival. It also uses myths to reinforce the city’s origin story. The Athenians took pride in their intelligence and systems of law and justice and having a temple a temple that is dedicated to the goddess that represents those qualities further reinforces that narrative. Another way the narrative of the Athenians being intellectuals is subliminally being told is through the use of columns. From the looks of the Parthenon, the columns seem to line up to make a perfectly straight line along the top of the columns, but that is actually an optical illusion. In reality, the columns are actually on a slight curve. The architects designed the building like this because if the columns were all literally the same size and on the same leveled platform it would look curved even though it actually is not. This architectural technique is call entasis. This again reinforces the narrative that Athenians were intelligent because it takes advanced mathematics and geometry to be able to counter act the tricks our eyes play on us. All of the narratives that this build is telling us have something to do with being an Athenian citizen. It gives a guideline for how you should present yourself during the festival and also reinforces the city’s origin story and religious beliefs through the depictions on the pediments.

The sixth architectural construction that will be looked at in this exhibit is the Great Altar from Pergamon, which was in modern day Turkey and has been reconstructed in Berlin. It was built from 166 to around 156 BCE by the order of King Eumenes II during the Hellenistic period, where Greek culture was being spread around the Mediterranean region. This alter was heavily influenced by the architecture and sculpture of the Classical Greeks. It is constructed entirely of marble in the Ionic order, evidenced by the columns. The Great Alter possesses a large set of stairs with a colonnade at the top of the steps. It also has multiple high relief sculptures on the east and west sides of it. These relief carvings depict several different scenes from Greek mythology. One of the friezes, measuring 360 feet long, is the Gigantomachy frieze, which depicts the battle between the Greek gods and goddesses and the Giants (Altar of Zeus at Pergamon). This battle held a lot of significance in the religion because it tells how the Olympians conquered the Giants and seized power for themselves. Another scene shows Athena and Nike teaming up to fight against the giant Alkyoneus and his mother Gaia. Like the other pieces of architecture in the exhibit that featured reliefs or sculptures in some way, these statues create a narrative that show the stories and myths in the physical form. By seeing the relief sculptures not only come out of the wall in to the three dimensional but do so in the Hellenistic style of sculpture, which featured a lot of twisting of the body and cloth that draped over the body with incredible realism, almost makes the sculptures appear like they are coming to life.

The seventh and final architectural achievement that will be examined in the exhibit is the Pantheon in Rome. Its construction originally was ordered by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in the year 27 CE, but it was burned down in a fire in 80 CE, leading to another Pantheon getting erected in the same spot as the old building. Unfortunately, this Pantheon was burned down yet again in 110 CE, so a third building was constructed and finished in the year 125 CE under the rule of Emperor Hadrian. The building was built in the Corinthian order. The purpose of the building is speculated to be a temple dedicated to all of the gods. “However, no cult is known to all of the gods and so the Pantheon may have been designed as a place where the emperor could make public appearances in a setting which reminded onlookers of his divine status, equal with the other gods of the Roman pantheon and his deified emperor predecessors (Cartwright).” If this is was what the building was actually for then the emperor was certainly trying to create a narrative that he was sending the citizens that he was a living god. Creating this narrative probably would make the citizens scared of him and follow his rule unconditionally. It also elevated him above everyone else, meaning the emperor could basically do whatever they wanted with no repercussion. Inside, the Pantheon had a rotunda, which was a circular type of room. The ceiling of this room is an unsupported dome, with an oculus at the top of it. An oculus was an opening in the ceiling that allows light in. When the light shines through the oculus it can give one the impression of having the gods staring down at them. This creates a narrative as well because if you believe the gods are literally peeking through the oculus to check that you are not up to no good you are probably a lot less likely to do anything that you thought that the gods would consider wicked out of fear of their painful wrath.

Works Cited

Alberto Siliotti. Guide to the Valley of the Kings. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1997

“Altar of Zeus at Pergamon (c.166-156 BCE).” Pergamon Altar of Zeus. Accessed April 22, 2015. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/antiquity/pergamon-altar.htm.

Brittany Garcia. “Ishtar Gate,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified August 23, 2013. http://www.ancient.eu /Ishtar_Gate/.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Ishtar Gate”, accessed April 23, 2015,http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/295381/Ishtar-Gate.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Pyramids of Giza”, accessed April 23, 2015,http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/234470/Pyramids-of-Giza.

German, Senta. “Khan Academy.” Khan Academy. Accessed April 23, 2015. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/ancient-near-east1/sumerian/a/ziggurat-of-ur.

Jenkins, I. “Central Scene of the East Frieze of the Parthenon.” British Museum -. January 1, 1994. Accessed April 23, 2015. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/c/central_scene_-_east_frieze.aspx

Mark Cartwright. “Pantheon,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified June 12, 2013. http://www.ancient.eu /Pantheon/.

“Panel: striding lion [Excavated at Wall of Processional Way, Babylon, Mesopotamia]” (31.13.2) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/31.13.2. (October 2006)

Robin Fowler. “The Great Pyramid of Giza: The Last Remaining Wonder of the Ancient World,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified January 18, 2012. http://www.ancient.eu /article/124/.

Silverman, David. “The Parthenon.” Parthenon. Accessed April 22, 2015. http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110Tech/Parthenon.html.

Sullivan, Mary Ann. “Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut.” Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut. January 1, 2001. Accessed April 23, 2015. https://www.bluffton.edu/~sullivanm/egypt/deirelbahri/deirelbahri.html.