The art historical community is locked in a decades-old struggle over defining rightful custody of found artifacts and objects that have been transported to other locations. Although well-trained art historians generally aim to be respectful of the country’s culture, a major area of disagreement concerns rightful ownership of the artifacts. The arguments supporting the opinions of authors Chas. Chaille Long and James Cuno are rather emotional, both equally valuing the integrity of the ancient artifacts and the original creators or worshipers. The descendants and traditions involved with the purpose of the objects need to be honored, but art historians need to be aware of the cultural significance of the objects. But the cultural significance of the objects will only be discovered through research. In two particular scholarly articles, two opinions are explored in the ongoing debate over ancient artifact ownership and shed light on major political and cultural issues surrounding the current status of ownership of antiquities.

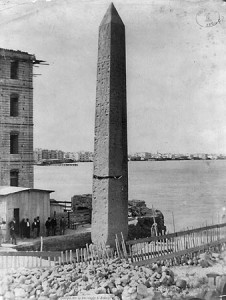

Ownership of ancient artifacts discovered today follows set laws by individual countries, which expect to be honored. UNSECO aims to enforce archaeological ethic and supports repatriation in efforts to keep peace and promote mutual respect and understanding. In “Send Back the Obelisk!,” Chas. Chaille Long builds on those intentions and reaches out to a sympathetic audience, calling upon nostalgia and asserting that the context of Cleopatra’s Needle was lost when it was removed from its original environment. Long goes on to question the motives of Alexandria, stating that he did not believe the that land erosion threatened the original base of the obelisk. Long eventually makes a case for repatriation due to the lost context and seeming lack or appreciation or adequate upkeep. In Culture War: The Case Against Repatriating Museum Artifacts, James Cuno explores the repercussions of repatriation and the rights of a single nation’s government to demand artifacts’ return simply due to the fact that they originated within their modern-day borders. Through these compelling arguments, the topic of antiquities ownership reveals the dilemma of finding a way to display, honor, and preserve artifacts and the ancient civilizations while respecting the traditions and valid ownership claims of the modern nations.

Long’s great concerns over the acquisition of Cleopatra’s Needle illustrates the abuses governments can create for nothing more than personal gain. In this case, the United States is the offender. However, his plea for repatriation of Cleopatra’s Needle seems to be presented without merit, and supports himself with repetitive nostalgia and insistence that the obelisk does not hold the same context as it does on its original foundation. The fact is that the obelisk was weathering in its original country of origin, and the government at the time was unwilling to make necessary repairs or any further concessions to protect the obelisk. Long asserts that repatriation will “save it from annihilation” (Long 5). The bold statement goes without much support, lacking proof or follow-up explaining exactly how sending the obelisk back to Egypt would result in preservation. The original environment in which Long wholeheartedly believes Cleopatra’s Needle belongs was actually a major contributing factor to the obelisk’s deterioration, citing that sand was a cause for weathering. With his own emotions and personal convictions clouding his judgment, preservation does not appear to be a major concern for Long.

When it comes to preserving an object that could otherwise be lost due to human or natural destruction, lost context seems trivial in comparison. The relocation of artifacts to more capable hands ensures the future ability to study and receive knowledge of early civilizations from the objects. James Cuno changes the tone, naming preservation of artifacts as a priority. He does support UNESCO and repatriation when used honorably, crediting repatriation for preventing illegal sales, looting and returning objects that were otherwise acquired dishonestly. But repatriation can have negative repercussions, specifically when a nation simply cannot provide proper housing, care or security. Regardless, some nations abuse repatriation and accusations of offending their ancestors, when in actuality the political structure’s main concern is profit from the artifacts. We cannot assume that every country claiming ownership of newly found artifacts and demanding repatriation of previously removed objects has the best intentions in mind. Assuming that a governing body cares for artifacts on a respectful, emotional level is a detriment to archaeology and hinders preservation. Cuno shares this viewpoint in his article, stating that “cultural property should be recognized for what it is: the legacy of humankind and not of the modern state, subject to the political agenda of its current ruling elite” (Cuno 3). Encyclopedic museums, such at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre, serve the greater good. With staff who are highly trained in preservation and in research on the background of the artifacts, the antiquities are in great hands while in museums. Major, well-developed countries provide a strong political structure and a military presence that better protects the objects, and their museums’ open doors to the general public provides the common people with widespread access

to knowledge and understanding of these early civilizations. In these cases of objects of such antiquity, the fact that the knowledge affects modern civilization today supersedes any present national borders and their claims of ownership. On the sensitive topic of religious customs, it is an arguable case that the dishonor of removing an object affects the spiritual value to not only the owner’s modern civilization, but to the original people and the religion itself. If the social and political atmosphere allows for cooperation, attempts should be made to conserve the artifacts on-site. The items serve a great historical importance when able to ideally exhibit them in their natural environment with international cooperation. However, not all governments have the ability to budget for a proper museum, curators, special amenities for handling and preserving artifacts, and strong security. We are currently witnessing terrorist organizations in Africa and the Middle East, namely ISIS and Boko Haram, who have no interest in preservation of ancient artifacts and respect for any kind of spiritualism other than their own. They instead are targeting artifacts with intent to destroy any objects they see as false idols that contradict their own religion. In extreme instances such as this, the government is unable to protect artifacts, and repatriation should not be considered for countries in political turmoil. An exception to any opinions on handling of artifacts should be the treatment of human remains; any human remains should first be considered as a human with a funerary custom, and the funerary custom of human remains should be honored.

The case Long made with Cleopatra’s Needle is a fine example of why ownership should not be given out of convenience, but rather bestowed to a responsible academic party that can both honor and properly care for ancient artifacts. Cuno took a different approach, lamenting how world leaders interfere with the furthering of the world’s understanding of ancient history simply for personal gain. After analyzing both viewpoints, the conclusion can be met where preservation of ancient artifacts is key and artifacts need to be in possession of a group of scholars that can assume responsibility for the preservation of the artifacts, not a convenient ownership decreed by a political government due to where their borders lie. To exhibit archaeological ethic and cultural understanding, art historians must respect the cultural significance of ancient artifacts; however, the advancement and benefit of our understanding of early human civilizations benefit the entire world through knowledge, and the politics of corrupt or misguided governments should not prevent discovery of human history.

By: Jennifer Crumby

Bibliography:

Cuno, James. “Culture War: The Case Against Repatriating Museum Artifacts,” in Foreign Affairs (Tampa, FL: The Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., 2014).

Long, Chas. Chaille. “Send Back the Obelisk!” in The North American Review (Cedar Falls, IA: The University of Northern Iowa, 2011).