Jesse Busby

Since the Greeks, there has been an emphasis on the human body. Whether it be exaggerated emotions and contorted posture or the idealization of the human form, we see countless reconstructions of Greek statues. The Greeks pointed sculpture in a direction it would continue to travel even through today.

Kouroi, the earliest of the large stone figures, were rigid and stiff as seen in Egyptian statues. These lifeless figures slowly evolved, and with great detail added to their musculature. Arms slowly begin to rise and their slightly leaning posture begins to bring movement to the sculptures. Eventually the Greeks get so realistic and miniscule in detail that the human form has reached perfection. This perfection didn’t emerge because the Greeks had an infatuation with perfect bodies. For the Greeks, reaching peak physical stamina was strived for. Greek city-states like Sparta and Athens placed so much emphasis on the thought of the perfect human form that they would discard infants if they didn’t meet the expectations of the time.

The sculptures of the ancient Greeks, Etruscans and Romans didn’t come about for the sole purpose of having something pretty to look at. These sculptures aren’t only alike in that they follow Greek methods, but also because they all reflect certain ideologies of the culture and society that produced them. For example: the influence the Greeks placed on physique; the light-hearted laissez-faire attitude of the Etruscans; or the importance of age, wisdom and experience for the early Romans. Every work of art we see from these societies is the direct response of their social and political way of life.

Dying Gaul

The Dying Gaul is an ancient Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic bronze sculpture. The original may have been commissioned some time between 230 and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Gauls, who were the people of Anatolia, which is part of what is now modern Turkey[1]. The identity of the sculptor has been attributed to Epigonus, court sculptor of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon, may have been the creator.[2]

marble, 37 x 73 7/16 x 35 1/16 in.

Sovrintendenza Capitolina — Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy

The marble statue shows a fatally wounded Gallic warrior with remarkable realism, putting emphasis on the strange posture of the body and the pain shown on the Gaul’s face. A bleeding sword puncture is visible below his right breast. The figure is shown with a torc around his neck, which represents his high status among the Gallic people.[3] He lies on his fallen shield while his sword, belt, and a curved trumpet lie beside him. An interesting aspect of this sculpture is how courageous and composed the Gaul looks, even on the brink of death. Though the Gaul does appear to be in pain, he is not represented as overly dramatic, like many other Greek statues around this time.

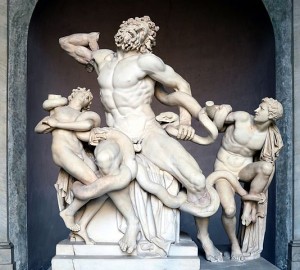

Laocoon and His Sons

As described in Virgil’s Aeneid, Laocoon was a Trojan priest. When the Greeks left the famous Trojan horse on the beach, Laocoon tried to warn the Trojan leaders against bringing it into the city. The Greek goddess Athena, acting as protector of the Greeks, was furious that Laocoon warned the Trojans about the horse. Athena punished Laocoon for his interference by having him and his two sons attacked by the giant sea serpents.[4]

Laocoön and his sons, also known as the Laocoön Group. Marble, copy after an Hellenistic original from ca. 200 BC. Found in the Baths of Trajan, 1506.

The emphasis on emotional intensity and theatricality is very common among Hellenistic sculptures. The amount of pain in Laocoon and his sons’ faces is the ultimate depiction of pain. Their bodies are depicted as perfect forms, as to match the exaggerated emotions on their faces. This sculpture represents Hellenistic art at its finest. The way the bodies are contorted in uncomfortable positions and the way Laocoon’s head is rolled back, placing strain on his neck, are similar to Athena Fighting the Giants from the Altar of Zeus, another Hellenistic sculpture.[5]

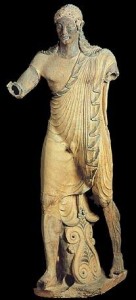

Apollo- Etruscan

The Apulu of Veii is a great example of Etruscan sculpture. Apulu, the Etruscan equivalent of Apollo, is a terracotta sculpture that is slightly larger than life-size from the Portonaccio Temple at Veii. The figure was part of a group of statues that stood on the ridgepole of the temple and depicted the myth of Heracles and the Ceryneaian hind.[6] The figure of Apulu confronts the hero, Heracles, who is attempting to capture a deer sacred to Apulu’s sister, Artemis. Of the remaining figures from the temple at Veii, Apulu is the most complete statue.[7]

Apulu of Veii. Painted terracotta. Ca. 510-500 BCE. Portonaccio Temple, Veii, Italy.

The figure of Apulu has several Greek characteristics, but there are a few differences that set the Etruscan statue apart. The face and position of the body are similar to that of Archaic Greek kouros figures. The face is simply carved and an Archaic smile provides a link to Greek influence. The hair of Apulu is stylized and falls across his shoulders and down his neck and back in simple, geometric twists that could possibly represent braids.[8] The statue, like Greek statues of the time, was painted using vibrant colors.

Unlike Archaic Greek statues and kouros, the figure of Apulu is shown with more body movement and more stylized muscles and clothes than that of the Greeks. Apulu is shown stepping forward, with an arm stretched out, possibly holding a bow that is no longer intact. Unlike Greek sculptures and portrayals of Apollo at the time, the Etruscans have clothed the figure, draping a toga over one of his shoulders.[9] The way the toga is represented clinging tightly to his body and the stylized folds of the fabric differ from that of the Greek’s over-exaggerated realism.

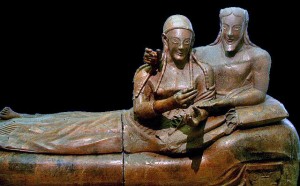

Sarcophagus of Spouses

A late sixth century sarcophagus excavated from a tomb in modern day Cerveteri is a terracotta sculpture depicting a couple reclining together on a sort of couch. The sarcophagus displays not only the Etruscan Archaic style but also Etruscan skill in working with terracotta. The figures’ torsos are modeled and their heads are in a typical Etruscan egg-shape with almond shaped eyes, long noses, and an Archaic smile.[10] The hair is stylized, as seen in Apulu of Veii, and the figures are shown making gestures. The Etruscans place a large amount of emphasis on gesture, both in sculpture and painting.[11] It is believed that the woman originally held a small vessel, maybe used for wine, and the couple appears to be intimate and happy due to the fact that the two are intertwined.[12] Greek art portraying a man and woman aren’t this light-hearted and loving. Generally, Greek art showing a man and wife has a more serious tone.

Aulus Metellus (the Orator)

After the fall of the kings of Rome, the Republic began to form, and in turn the emphasis on realistic portrayals of public officials.[13] Fearful that the Republic could take back power from the people, seeing the statues of figures of power portrayed like a regular roman citizens restored hope that the leaders are there as an extension of the common Roman. The bronze statue Aulus Metellus was one of the statues used to speak to the people, assuring them that the Republic was working in their interests.[14]

The life size statue of the Roman official stretches his hand out toward the crowd he is addressing. With his arm outstretched toward the people, the official is letting the public know that he has the power and authority to help them voice their opinions.[15] The way the statue is posed makes him appear more like one of the people rather than someone that is of higher status. His toga is neatly folded and draped around his body, marking him as a governmental official, but the way his garments are shown so naturalistically also supports the idea that this figure doesn’t see himself as an elevated official.[16] The figures features and body are very common, unlike Hellenistic and other Greek figures, showing the human form in perfection. Viewers would be able to identify with this statue and place their trust in this man. The portrayal of senators and officials as caring and strong individuals helped restore trust and ease the tension on the Republic’s political system.[17]

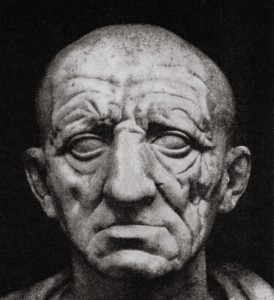

Portrait bust, Cato the Elder

The portrait bust of Cato the Elder, from Otricoli (ancient Ocriculum) dates to the middle of the first century B.C.E. The portrait is a powerful representation of a male aristocrat with a strong roman nose.[18] The figure is shown lacking emotion, letting the wrinkles and scars do the talking. The figures abundance of wrinkles, a strong brow, and sunken skin, characterize the portrait head. The Romans used this veristic style of portraiture to show how wise and experienced the figures were, which were very influential characteristics to have.[19]

Head of a Roman Patrician. From Otricoli, Italy. Ca. 75-50 BCE.

Though this bust may seem unappealing by today’s standards, the portrait of Cato the Elder would have made for an influential piece while participating in the elections of the Republic. The physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating the way in which the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors.[20]

Augustus Primaporta

Roman art and politics often go hand in hand. This is easily visible when viewing portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire. Augustus used the power and influence of imagery in his portraits to spread his ideology across the Roman Empire.[21] One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is Augustus of Primaporta (20 B.C.E.).

Flickr user: russavia

Augustus of Primaporta

In this marble freestanding sculpture, Augustus stands in a contrapposto position (a relaxed pose where one leg bears weight). The emperor is wearing armor with his right arm extended, demonstrating that he may be addressing his soldiers or some sort of crowd.[22] Already, this sculpture gives off a sense of power and status, differing from previous roman figures such as Cato the Elder and Aulus Metellus.

Delving further into the composition of the statue, an obvious resemblance to the Greek sculptor Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, is clear.[23] Both sculptures are shown in a similar contrapposto stance, and both figures are idealized. Like Doryphoros, Augustus is also portrayed as youthful and flawless. Augustus is shown as youthful and in great shape, though he was well past his prime at the time of the sculpture’s commissioning.[24] Augustus has tried to link himself to the golden age of the Greeks by associating himself with the idealized body and posture of the Doryphoros.[25]

Bibliography

“National Gallery of Art.” The Dying Gaul. November 26, 2013. Accessed April 17, 2015. http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/press/exh/3655.html.

“Laocoon and His Sons (c.42-20 BCE).” Laocoon and His Sons, Greek Statue: History, Interpretation. January 1, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2015. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/sculpture/laocoon.htm.

“Archaic Art.” Boundless Art History. Boundless, 03 Jul. 2014. Retrieved 15 Apr. 2015 from https://www.boundless.com/art-history/textbooks/boundless-art-history-textbook/the-etruscans-7/early-etruscan-art-68/archaic-art-356-5528/

“Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.” Arthistoryoftheday. August 19, 2011. Accessed April 18, 2015. https://arthistoryoftheday.wordpress.com/2011/08/19/aulus-metellus-late-2nd-or-early-1st-century-bce/.

Becker, Jeffrey. “Khan Academy.” Khan Academy. Accessed April 19, 2015. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/roman-republic/a/head-of-a-roman-patrician.

Fischer, Julia. “Khan Academy.” Khan Academy. Accessed April 19, 2015. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early-empire/a/augustus-of-primaporta.

[1] “National Gallery of Art.” The Dying Gaul. November 26, 2013. Accessed April 17, 2015.

[2] “National Gallery of Art.”

[3] “National Gallery of Art.”

[4] “Laocoon and His Sons (c.42-20 BCE).” Laocoon and His Sons, Greek Statue: History, Interpretation. January 1, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2015.

[5] “Laocoon and His Sons (c.42-20 BCE).”

[6] “Archaic Art.” Boundless Art History. Boundless, 03 Jul. 2014. Retrieved 15 Apr. 2015

[7] “Archaic Art.”

[8] “Archaic Art.”

[9] “Archaic Art.”

[10] “Archaic Art.”

[11] “Archaic Art.”

[12] “Archaic Art.”

[13] “Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.” Arthistoryoftheday. August 19, 2011. Accessed April 18, 2015.

[14] “Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.”

[15] “Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.”

[16] “Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.”

[17] “Aulus Metellus, Late 2nd or Early 1st Century BCE.”

[18] Becker, Jeffrey. “Khan Academy.” Khan Academy. Accessed April 19, 2015.

[19] Becker, Jeffrey

[20] Becker, Jeffrey

[21] Fischer, Julia. “Khan Academy.” Khan Academy. Accessed April 19, 2015.

[22] Fischer, Julia

[23] Fischer, Julia

[24] Fischer, Julia

[25] Fischer, Julia