By Carly Gagstetter

Since the dawn of human existence, the topics of love and death have heavily shaped many cultures. In fact, many archaeologists use grave goods and the state of burial grounds to determine the priorities of a society that they are studying. There were many classic myths from Ancient Greece that depict both of these topics, often beautifully intertwining them. One of the common tropes in the Greek mythos that displays this meshing is the death of the maiden. The tales of Orpheus and Eurydice, and The Rape of Persephone embody this trope. One tells the tale of a loss of romantic love, the other of familial love. Both myths combine both the themes of love and loss in a classic way, inspiring many works of art even to this day.

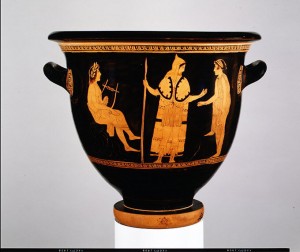

Orpheus is arguably the most famous magician in the Greek mythos, second only to the God Apollo. He was born to the muse of epic poetry, Calliope and was gifted with an uncanny ability to play the lyre. Hardy Fredricksmeyer his music as “So powerful that its influence extends beyond the human realm to enchant wild animals, stop birds in flight, and uproot rocks and trees” (Fredricksmeyer 253). He was to marry the lovely Eurydice, but on their wedding day she unexpectedly perished due to being bit by a venomous snake. In his Metamorphoses Ovid writes, “Inflam’d by love and urg’d by deep despair,/He leaves the realms of light and upper air;/Daring to tread the dark Tenarian road;/And tempt the shades in their obscure abode;/Thro’ gliding spectres of th’ interr’d go,/And the phantom people of the world below” (Ovid 10.17-22). Orpheus, consumed by grief, decided to make the descent into the underworld in order to save his beloved Eurydice. There he ran into Hades and Persephone, the king and queen of the underworld. Due to his beautiful musical prowess, he was able to charm the god and goddess into agreeing to allow him to take back Eurydice to the world of the living. There was one condition to this pact, however. Until they reached the surface and the world of the living, Orpheus would not be allowed to look back at his wife. The musician agreed to the terms and fetched his wife. Just as they were coming up to the surface, Orpheus broke his promise and turned around. There he saw Eurydice in a grotesque state of both life and death, a secret that no human should be allowed to see. Hades and Persephone reclaimed the soul of Eurydice, and Orpheus met an untimely end. Some sources say that he was torn apart, either by animals or the Maenads, and others say that Zeus himself struck him down in order to keep him from repeating the secrets of the underworld. In the terra cotta vessel pictured above Orpheus, pictured with his lyre, is awaiting his fate at the hands of the woman with the sickle. According to John MacQueen, “Eurydice has an ambiguous, and even sinister, significance. She is the thought which Orpheus sought to lead to the light above; she is also the desire which turned him back to darkness from the bounds of light” (MacQueen 261). The themes of light and dark appear often, not only during the course of lost love myths, but in tales of heroic journeys. Orpheus during the tale of The Death of Eurydice could fall into the heroic pattern, due to his journey into the underworld. This trope has been seen among many stories of heroism throughout human existence. In fact it is such a common theme that it is even a part of Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth, or The Hero’s Journey. One can even say that his performance for Hades in an attempt to gain back the soul of his late wife could fall under the stage of the monomyth called the atonement with the father. The atonement is described as the “stage the hero confronts a being with immense power that represents both the hero’s God, his superego, and his sins, his repressed id” (Reidy 215). However, Orpheus’ journey deviates slightly from the heroic format, as he is murdered at the end. One could claim that his death was not in vain, as he was finally reunited with his wife, Eurydice, in the afterlife. While the terra cotta vessel depicts and ominous scene on the cusp of the bard’s demise, the admirer must remember that his death is not the end of his story.

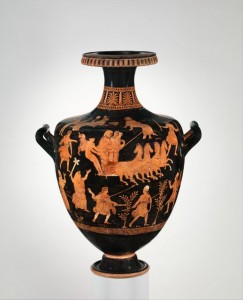

While the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is about the struggles of romantic love and loss, the myth of The Rape of Persephone tells about motherly love in the context of loss. Persephone, also called Kore, was a young maiden. She was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, and was much beloved by her mother. One day the girl was out with her friends, picking flowers in a meadow. In Greek mythology, meadows and flower picking tend to be symbolic of the transition from maidenhood to womanhood. Susan Deacy describes the Greek meadow as “a place of sexual allure, whose sensual pleasures emanate from the visual appeal of the flowers combined with the heady scent generated by their profusion” (Deacy). Persephone was engaging in these activities when she came upon a lovely and large narcissus bloom. When Kore went to reach for the flower, Hades sprung from the earth on his chariot and swept her away to the underworld. Demeter was devastated over the disappearance of her daughter. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, it is said that for nine days she “wandered the earth with flaming torches in her hands, so grieved that she never tasted ambrosia and the sweet draught of nectar, nor sprinkled her body with water” (Homer 2. 44-46). As Demeter was a goddess of fertility and the harvest, her despair caused crops to die around her. With help from Helios and Hecate, Demeter was able to locate her daughter. However, since Persephone had consumed pomegranate arils in the underworld, she would not be able to fully return. Instead, Demeter and Hades struck a deal. For half of the year Persephone would stay with her mother in the world of the living and the plants would grow and prosper. For the other half of the year, Kore would remain in Hades with her husband, and the crops would wither and die. There are many facets to the tale, as it is both an explanation for a natural phenomenon, symbolism for the loss of innocence tied to maturation of women, a lamentation of a mother’s love, and a cautionary tale. In the terra cotta vessel above there is a vivid depiction of Persephone’s abduction, and the chaos that was created in its aftermath. The middle of the vase depicts Hades’ chariot: the very one used to abduct the young Kore. Around the chariot scene are many of the other gods including, Hecate with her torches, Aphrodite and Eros encouraging Hades’ lust, as well as Demeter and Athena. There are also stalks of grain, which play on the themes of fertility and growth that are heavily relied on in the myth. The tale of Persephone and Demeter also influenced one of the largest cults in the ancient world: the Eleusinian Mysteries. The cult was said to have to do with “benefits of some kind in the afterlife” (Encyclopedia Britannica). In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter the mysteries are described by saying “Happy is he among men upon earth who has seen these mysteries; but he who is uninitiate and who has no part in them, never has lot of like good things once he is dead, down in the darkness and gloom” (Homer 2.476-478). The story of Persephone and Demeter, like the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, involve a journey from maidenhood to the afterlife. This is symbolism for the loss of innocence and childhood whimsy that comes with marriage and reaching childbearing age. While it marks the end of one era, it ushers in the next. The afterlife was seen as a necessary step in the journey of life, just as marriage is to a woman. Adding to the themes of loss of innocence, the pomegranate is often seen as a symbol for testes; they are full of red and life giving seeds surrounded by milky white flesh. Between the picking of the flowers and the consumption of Hades’ arils, it is quite clear that Persephone was no longer an innocent maiden.

Much insight into the Greek culture regarding its views on love and loss, as well as maidenhood and the heroic cycle just through the stories of Orpheus and Eurydice and The Rape of Persephone. Both tales place a great deal of emphasis on the severity of the cross into womanhood and the loss of a maiden’s innocence, and both are depicted many times in art throughout the years. Love, whether it be romantic or familial, is a basic human emotion; the loss of that love can wreck even the strongest man deep down into his core. Orpheus was willing to risk his life to dive into the underworld to save his beloved, and Demeter crippled herself by denying her personal needs while consumed by her grief. Even as an immortal god, her refusal of both ambrosia and nectar severely weakened her body and mind. Because of the pandering to basic human emotion, the myths resonate deeply in the souls of those who consume them. Parents gasp in horror at the idea of the literal loss of a child, and many an older parent can even relate to the idea of losing their child to marriage. Anyone who has been in love before gawks at the thought of losing their beloved, many even side with Orpheus’ actions after the loss of his wife. And while many mock him for disobeying orders and turning around to get a look at Eurydice, the deep ache of not knowing whether or not she was actually following him would be too much for the average person to bear. It is human nature to grieve, to turn around to face the unknown just to make sure that a loved one would be okay. Parent to child, lover to lover, these emotions lie within us all and shape our very lives and very world. The ideas portrayed in Ancient Greece still affect the very lives that we as a society live in today.

Works Cited

MacQueen, John. “Article by John MacQueen.” Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800 20 (1993): 261. Accessed April 12, 2015. http://go.galegroup.com.libdata.lib.ua.edu/.

Publius Ovid Naso, Metamorphoses, trans. Garth, S.; Dryden, J.; et al. London. 1717.

http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.html

Fredricksmeyer, Hardy. “Black Orpheus, Myth and Ritual: A Morphological Reading.”International Journal of the Classical Tradition 14, no. 1/2 (2007): 148-75. Accessed April 12, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/.

Reidy, Brent. “Our Memory of What Happened Is Not What Happened.” American Music 28, no. 2 (2010): 211-27. Accessed April 12, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/.

Evelyn-White, H.G. “Homeric Hymns.” Classical E-Text: THE HOMERIC HYMNS 1. January 1, 2011. Accessed April 13, 2015. http://www.theoi.com/Text/HomericHymns1.html#2.

Deacy, Susan. “From “Flowery Tales” to “Heroic Rapes”: Virginal Subjectivity in the Mythological Meadow.” Arethusa 46, no. 3 (2013). Accessed April 12, 2015. http://muse.jhu.edu.libdata.lib.ua.edu/.

“Eleusinian Mysteries.” Encyclopedia Britannica.