Ma’at: The Goddess and Principles of Truth and Wisdom

Ma’at is both a significant Ancient Egyptian goddess and a series of essential principles representing truth, justice and order. Her use in Ancient Egyptian life and religion is as diverse as her name’s multiple spellings. She appears in Ancient Egyptian religion as both a person and an intangible idea of cosmic balance among people and gods alike. Ma’at appears in two forms: “…as an abstract idea (maat) and as an anthropomorphized goddess Maat” (Faraone and Teeter 4). In physical goddess form, Ma’at is seen “…as a slender, idealized woman whose head is topped with an ostrich feather…In some representations, the plume is fastened to her head by a narrow fillet, while statues often show the feather emerging directly from the top of her head. The goddess usually wears a tightly fitting dress without ornamentation” (Faraone and Teeter 11-12). As an intangible idea, maat is “a moral and ethical principle that all Egyptians were expected to embody in their daily actions toward family, community, nation, environment, and god” (Martin 2). Given her purpose, a physical depiction of Ma’at was often seen in funerary art, where she served a pivotal role in Osiris’s judgment of the dead. She is easily identified by her signature long ostrich feather.

The idea of maat is extremely important in the overall and everyday lives of Ancient Egyptians. “According to the Egyptian religious conception, both man’s happiness and his virtue are guaranteed if he lives in harmony with Maat. This harmony requires both insight and wisdom. It is jeopardized by foolishness” (Bleeker 6). The principles of Ma’at could easily be described as a series of moral codes that guide everyday life based on Ancient Egyptian religion, declaring that a well-balanced life would determine how they were spiritually judged at death. The overall character of people on earth determined good fortune and favor of the gods based on the balance and order within their city. “Though the individual soul was justified for living maat, it was the community on earth that received direct tangible benefit” (Martin 13).

Kings of Ancient Egypt had a very important role to play in religious practices, which included Ma’at. A king’s ascension and succession establishes and continues cosmic order, or maat. Kings were essentially responsible or keeping things peaceful and well-balanced. To be specific, “the king’s offering of maat to a deity encapsulated the relationship between humanity, the king, and the gods; as the representative of humanity, he returned to the gods the order that came from them and of which they were themselves part” (Britannica 3). The importance of maat to the king’s rule is likely why many kings added “maat” to their coronation names.

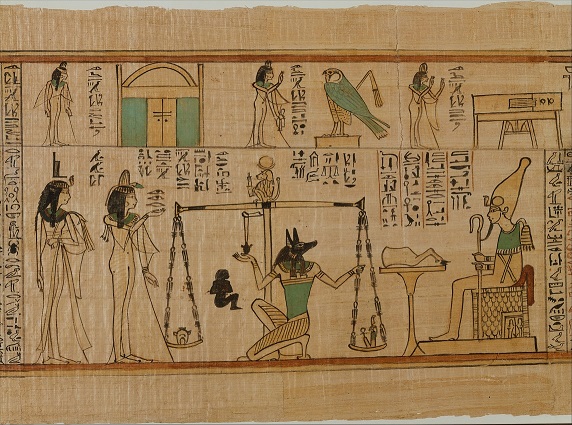

This artifact is The Singer of Amun Nany’s Funerary Papyrus, found in the tomb of an elderly Ancient Egyptian woman named Nany, and is currently in exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It bears a representation of the goddess Ma’at at the Weighing of Souls, a key part in the Judgment of the Dead. The scene shows an actual scale used by Osiris to weigh the tomb occupant’s heart. This scene is found in many funerary papyri. In funerary practices, the heart was left in the body for the sole purpose of Osiris weighing it against Ma’at or her ostrich feather as a counterbalance to judge how true to maat the heart’s owner lived his or her life. “If the deceased lived in accordance with maat, his or her heart would be a little lighter than the feather” (Martin 11). If they failed the weighing, a soul would die a second time and be banished from the cosmos. In this object, Ma’at is represented inside the scale to the right as a tiny figure or object. This papyrus clearly shows a blurred line between Ma’at’s representation as a goddess and as principle. While the representation is more of an object than a deity, such as how Osiris is depicted, the representation of the object itself is in a human form. Ma’at was given the same respect in everyday Ancient Egyptian life, serving both as a goddess and as guiding principles essential to achieving order and happiness in both life and everlasting life.

– Jennifer Crumby

Bibliography

Bleeker, C.J. “Guilt and Purification in Ancient Egypt.” In Numen, Vol. 13, p. 81-87. The Netherlands: BRILL Publishing House, 1966.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Egyptian religion,” accessed March 9, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/180764/Egyptian-religion/68285/King-cosmos-and-society.

Faraone, Christopher A. and Emily Teeter. “Egyptian Maat and Hesiodic Metis.” In Mnemosyne, Fourth Series, Vol. 57, p. 177-208. The Netherlands: BRILL Publishing House, 2004.

Martin, Denise. “Maat and Order in African Cosmology: A Conceptual Tool for Understanding Indigenous Knowledge.” In Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 38, No. 6, p. 951-967. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2008.