All rights to the Indiana Jones franchise © Paramount Pictures.

Jennifer Crumby

The Great Debate: Final Conclusions of Encyclopedic Museums and Ownership

Throughout this course we have looked into a vast collection of ancient structures and artifacts that create an idea of how we depict the early civilizations of the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia, ancient Egyptians, and the ancient Greeks. Through studies of these objects and preserved archaeological sites, art historians have pieced together what we believe to be accurate depictions of how these societies lived and ruled the Near and Middle East and Africa. From found artifacts we can learn how these ancient people farmed and hunted or fished, reproduced, bathed, traveled, communicated, and how they otherwise generally lived everyday lives. The study of the uses of these objects also reveal the economy or geography of the area at the time. Objects also commonly lead to discovery of liturgical purposes, such as icons for devotion and funerary practices. These artifacts and tombs also serve as primary sources for a historical map to the rulers of kingdoms. With the uncovering of artifacts we can study the advancement and political structures of these early civilizations, giving us insight into the world of our ancient predecessors.

A recurring topic has been the issue of rightful ownership and the legality of how ancient artifacts in museum and private collections were acquired. A hotbutton issue in the world of art history and the political sphere is the advocacy of encyclopedic museums. Museums are sometimes defended as sanctuaries for found objects, and at other times seen as thieves from the original lands of the artifacts’ perceived rightful owners and their descendants. While open discussion has proven that the general feeling is that any resolution should honor these ancient civilizations and the contextual significance of these objects, no clear consensus has been reached as to where these objects rightfully belong. As ancient predecessors to every human being on Earth, these objects demonstrate a sociological understanding of these early civilizations that benefit the world and history in its entirety. Without a doubt, we would not know much at all about these ancient civilizations without the discovery and allowed study of the objects, structures and geographical locations. Together we will analyze seven key historical objects whose significance of contextual meaning, amount of respect given in its current confinements, and rightful ownership are currently being questioned.

© Musée du Louvre, Paris. This image is for non-commercial scholarly use.

The Stele of Hammurabi is a six-foot-high monument made of black dolomite. It bears an image of the King Hammurabi receiving powers bestowed upon him by the Ancient Sumerian Sun God Shamash, c. 1792 to 1750 B.C.E. King Hammurabi ruled Babylon from 1782-1750 BCE and conquered around 1,000 square miles of present-day Iraq, cementing Babylon as a formidable ancient city. But what has made King Hammurabi most memorable was that he placed many monuments like this stele in his Babylonian cities, all which reminded the Babylonian people of their civic and religious duties to live by the Code. The Hammurabi Code was an impressive, highly developed ancient Sumerian legal system.

An article by Donald G. McNeil examines the Stele of Hammurabi’s inlaid Code of Hammurabi. McNeil does a wonderful job of examining King Hammurabi in-depth through this ancient stele’s coded legal system, judging King Hammurabi’s fairness and the authority exerted during his thirty two-year reign of Babylon. The breakdown of the Code of Hammurabi does thoroughly analyze King Hammurabi’s legal system and its rudimentary pre-Bible and pre-Democracy systems of checks and balances, but it is the author’s other outline that is of great interest to the topic of rightful ownership. McNeil introduces a fine detailed account of the discovery of the Stele of Hammurabi. Found in the ancient Persian city of Susa, now in Iran, the Stele of Hammurabi was discovered by a man by the name of M. deMorgan. According to McNeil’s account, M. deMorgan was the director general of an expedition sent by the French government to Susa on an archaeological dig in their interests (McNeil 444). It was during this expedition in 1901-1902 that they discovered the Stele of Hammurabi. It was in horrible shape, having been found in three separate pieces. deMorgan and his company of archaeologists joined the pieces back together to form what we now know as the Stele of Hammurabi, effectively preserving what’s left of the ancient artifact. From there art historians have been able to study the piece in cuneiform and reveal the earliest known example of a highly developed legal system in an ancient civilization.

The Stele of Hammurabi currently sits on display in the Louvre. The ancient artifact is safely preserved and exhibited to the public in an easily accessible and high-traffic encyclopedic museum, which happens to one of the world’s most popular museums. The Louvre also makes available digital images of the artifact online and in publications, as well as extensive information known about the object and King Hammurabi. This ancient artifact was unearthed from Iran in pieces and restored, the first time anyone of what we consider modern culture had ever seen this ancient stele. Without the questioned archaeological digs performed around a century ago, archaeologists may have never found ancient artifacts like the Stele of Hammurabi. These found objects were taken from the country of origin with permission from the ruling government of the time, breaking no laws and without use of any questionable ethics. Given that this artifact has been in the care and ownership of another country for over 100 years, has been made easily accessible to the public and to scholars, has been researched thoroughly to the advantage of the historical value of all mankind, and seems to be well preserved in a facility better than the country of origin can provide; any request to claim ownership of this particular artifact or otherwise remove the Stele of Hammurabi from the Louvre is currently unfounded. While it can be said that the contextual meaning is lost outside its land of origin, the Stele of Hammurabi’s context is long since gone. The original use was to outline the Code of Hammurabi during its reign. The current political structure of Iran hardly still adheres to the laws and religious practices of the ancient Babylonian era. Where contextual meaning is concerned, that has long since passed. As for a point of rightful ownership, the Iranian people cannot definitively prove without a doubt that they are completely straight descendants of this ancient Sumerian civilization only. Nor should the thousand of years between this modern era and this ancient civilization bestow any inheritance of this magnitude on the residents that currently occupy the region in which the ancient artifacts were first uncovered. In yeat another perspective, this region is currently experiencing a radical political and religious uprising tht has directly sanctioned the destruction of artifacts from ancient civilizations. The country of Iran is still experiencing an internal uprising, and cannot be considered a stable country capable of protecting ancient artifacts. In these instances, art historical preservation organizations such as UNESCO, who cooperate on an international scale with the United Nations, should be called in to mediate discussions and assist in a peaceful resolution to any dispute or analyze when to remove items due to threats of safety and preservation.

Ownership now © The Museum in Cairo, reused here for non-commercial scholarly use only.

Being one of the most famous and influential archaeological discoveries of the 20th Century can easily be attributed to the uncovering of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. In 1920, the determined archaeologist Howard Carter continued digging his way through the Valley of the Kings, eager to uncover anything left to be found. Where many other archaeologists accepted that nothing more of value was left to be found, Howard Carter found the sponsorship of English Earl of Caravon. The Earl of Caravon was himself an amateur explorer who had plenty of financial backing to keep Howard Carter digging. In January 1922, after two long years of digging and admittedly on the verge of giving up, Howard Carter and his team of excavators uncovered the tomb of a then-unknown young pharaoh.

The Mask of Tutankhamun, c. 1327 BCE, is a solid gold-encrusted mask from the innermost coffin of King Tutankhamun’s elaborate set of sarcophagi in his burial tomb. The mask is believed to be a representation of King Tutankhamun’s face. It bears lapiz lazuli and quartz motifs to define the brow and eyes. Now deconstructed, this innermost coffin’s mask is one of the most iconic images from the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. With Howard Carter’s discovery of the first fully intact tomb of an Egyptian pharaoh and previously discovered funerary artifacts and pieces displaying King Tutankhamun’s name, this fully intact mummy gave scientists and art historians most of the information that is known today of the process of mummification and other funerary practices of the ancient Egyptians.

The British Museum in London originally transported many of the found contents of King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber to London to be put on display. This mask and many other ancient artifacts appeared in a gallery opening in 1929, which was an enormous hit with historians and patrons. Queen Elizabeth II visited the 1929 exhibition and viewed Howard Carter’s discoveries herself. Through much controversy of Howard Carter’s taking of the tomb’s contents and England’s long-upheld claims to ownership of the tomb contents, as well as many world tours around the globe, the items and King Tutankhamun’s remains are now back in Egypt and under ownership of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo.

An article by John H. Douglas lays out many details of artifacts found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Douglas also mentions a little bit of details revealed by Howard Carter and the press as he uncovered the tomb and eventually took these artifacts as his own. The discovery and ultimately the removal of the contents of King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber have been well-documented by Howard Carter and member of the press of 1922. The Egyptian government at the time of discovery did not represent the sentiments of the Egyptian government that rules today. The inhabitants of Egypt today are understood to be the descendants of the ancient Egyptians, even being home to a radical sect of Egyptians who choose to follow the religion and other customs of the ancients. Egypt itself has been found to be capable of hosting, displaying, and preserving ancient artifacts and structures. The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities have many of these items on display to the public and still negotiate to make items available for further research, such as the famous x-ray CT scan that led to a forensic team’s digital facial reconstruction of what we believe to be King Tutankhamun’s true face. Given the amount of availability, preservation, and respect given to King Tutankhamun’s belongings and remains, the Cairo museum continues to prove that they are quite capable of handling the responsibilities that come with being bestowed the ownership rights of the ancient artifacts of one of their ancient pharaohs.

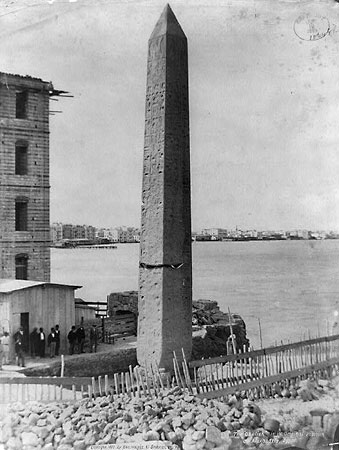

A solemn look at the deterioration of ancient artifacts leads us to a Cleopatra’s Needle monument, located outdoors in New York City’s Central Park. In Chas. Chaille Long’s article “Send Back the Obelisk,” Long recalls his first-person account of witnessing the unveiling of the Cleopatra’s Needle at its inception in the current installation on Central Park. He then recalled his first seeing it in Egypt during his military service, emotionally stating that the monument no longer evoked the civic and other ethereal meanings he once asociated with it. Additionally, according to Long, the context of Cleopatra’s Needle was lost when it was removed from its original environment. It was damaged in transport and was enduring weathering in its new place in Central Park. Deterioration or destruction of an ancient artifact is exactly hat needs to be prevented, and is a serious enough case that an advocacy or preservation group should step in to protect the ancient artifact. Likewise, returning the monuments simply for re-installation and allowing these monuments to continue to be weathered down and destroyed should be considered irresponsible and unacceptable in the art historical and historical preservation communities. In situations like these, deliberations with political leaders and groups such as UNESCO should take place to have peaceful resolutions. Preservation of the obelisk in the United States should be the key issue, and any rightful owner should be ready and able to provide preservation of the obelisk.

Although well-trained art historians generally aim to be respectful of the country’s culture, the area of disagreement is rightful ownership of the artifacts. While it is easy to sympathize with a group of people who feel disenfranchised over actions of something being taken from their land, that premise of sympathy is based on spiritual meaning. We cannot assume that every country claiming ownership has the best intentions in mind. Assuming that a governing body cares for artifacts on a respectful, emotional level is a detriment to archaeology and hinders preservation. We have to examine the country’s ability to preserve the sites or objects. ISIS and Boko Haram are reportedly uniting. A part of the militant terrorist groups’ “cultural cleansing” campaigns includes ridding nations of artifacts from other religions or civilizations – deliberate destruction of ancient artifacts. In the event of armed conflict, UNESCO cites The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Properties in the Event of Armed Conflict of 1954 for setting standards for discussing risks of leaving the artifacts, which are currently being destroyed by radical Islamic terrorists. In this case, preservation cannot be guaranteed. Though not enough evidence is currently provided to warrant a return of Cleopatra’s Needle, preservation should be the responsibility of the current owners of the monument.

The statue of Hatshepsut, c. 1479 to 1458 BCE, is located in the British Museum in London. It is carved from limestone and originally was further decorated with paint. The statue was uncovered in Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, which is the location of her temple. Though damaged quite a bit when it was recovered, it is still a mainly intact and wonderful representation of a female pharaoh. As Hatshepsut reigned further, physical depictions of the queen began to change. A published 2006 museum review by Emily Teeter beautifully describes this and many other physical depictions of Hatshepsut, along with a nice description as to what we know historically from her reign. Images of Hatshepsut began a metamorphosis of her gender, changing some of her body style to resemble more of a masculine form without much subtlety. Her female breasts smooth out to a more masculine chest, she wears a male ceremonial kilt, and she sports a false beard which a female most definitely could not have grown herself. The damage could be attributed to the destruction of some of her monuments by her stepson Thutmose III, who harbored a great deal of animosity towards his stepmother after she usurped his throne a little while after he came of age to assume the title of King. Accordingly, mentions of Hatshepsut became scarce likely at King Thutmose III’s wishes. Hatshepsut’s temple, the Hathor Chapel, was a target of his anger, and archaeologists can see why. Inside the temple are inscriptions announcing her accomplishments and a message from her celestial father delivering the message that his daughter is a wonderful king and reinforcing her right to rule as she did.

This statue was recovered from Thebes in 1845, though not intact. Other pieces were recovered approximately 80 years later and were rejoined with the original piece, which was located in Berlin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art then negotiated to acquire the main piece to restore the statue. An expensive and painstaking process from excavation to restoration, a great deal of care and responsibility has been put into this statue of Hatshepsut by the museum. As a queen who achieved the rare title of a female pharaoh, a statue such as this is extremely important in terms of historical research. This ancient artifact, along with primary scholarly sources, arguably proves that such a person very likely existed. The current condition of the statue causes enough alarm that preservation not only should come first, but that whichever museum, no matter which country, appears to be the most stable and has the best conditions for preserving this artifact should do so with ownership and accepted responsibility of the object, along with the technology and other capabilities that only a major museum could handle.

An example of an international group at work is UNESCO. The work they have accomplished with on-site preservation includes the Great Pyramids of Giza in Cairo, Egypt. Constructed between 2575 and 2465 BCE, the Great Pyramids have been called architectural and engineering marvels, as well as one of the seven wonders of the world. Extremely similar to ziggurats, these structures serve as burial tombs of pharaohs. UNESCO is an acronym for United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO designated these famous pyramids as a protected World Heritage site in 1979. That proclamation came in handy in 1995 when the Giza Pyramids were threatened by way of destruction for a highway project in Cairo. When contemplating how Egyptians could consider doing such a thing, we must remember that these ancient pyramids actually run flush to the outskirts of a present-day densely populated city of Cairo.

UNESCO was able to complete this task with the World Heritage Convention: a subgroup inside UNESCO that takes immediate action to preserve any World Heritage site that is in danger of destruction. Negotiations with the Egyptian Government resulted in a number of alternative solutions which replaced the disputed project. UNESCO does not claim ownership, but instead negotiates for the protection of World Heritage Sites and empowers groups within the countries to work with their governments to preserve historical sites.

Another example of a key historical monument that is now considered to be in danger is the Temple of Ishtar in the city of Ashur, located approximately 100 kilometers outside Mosul in present-day northern Iraq. The Assyrian city of Ashur was a key city during the Akkadian empire that ruled c. 2334 to 2154 BCE, and was eventually the capital of Assyria. While smaller than Nimrud and Nineveh, it sat at a pivotal position along a trade route in Mesopotamia that aided in supporting a strong economy that guaranteed the city’s survival over centuries. Another element of this particular ancient city was its geographical benefits. This particular city was erected flush to the Tigris River, and the city’s other unique geographical surroundings afforded the city natural defenses which were strengthened with buttressed walls. Ashur was one of the earliest forts ever uncovered from ancient early civilizations. Ashur is also the site of the Temple of Ishtar or Inanna of Ashur, where a large cache of ancient artifacts were unearthed by excavator Walter Andrae.

Looking at an article discussing Assyrian artifacts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and previous installments in Berlin, we can see that many found object from the discovery of the Temple of Ishtar in Ashur are currently preserved and protected within encyclopedic museums. Considering the armed conflict currently plaguing Iraq and the imminent danger ancient artifacts face from the radical terrorist groups, ownership is no question. Of the many ancient artifacts from Ashur in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, some were objects from the uncovering of the Temple of Ishtar. From just this temple we discovered votives and statues depicting gods, rulers and other objects that have been studied and benefited our understanding of rituals and everyday lives of the ancient Sumerians. A discovery of ancient artifacts found underneath the temple was very valuable to research. Excavator Walter Andrae uncovered items such as copper objects, clay statues, glasswork and precious stone jewelry. These significant ancient artifacts demonstrate metalwork and glass and jewelry-making skills of the Assyrians and their predecessors.

The rising power of radical forces and the beginning of the Iraqi-American War assisted UNESCO in making the decision to make the city of Ashur and its Temple of Ishtar a World Heritage Site in 2003 in efforts to further protect the site from damage or destruction. UNESCO submits that the ancient city provides scholars the opportunity study the evolutionary engineering practices of the ancient Sumerians. Right now northern Iraq is in immediate danger from the sanctioned destruction of ancient artifacts by the radical religious group ISIS, who aim to eradicate artifacts from ancient civilizations that did not worship their god. In March of 2015, UNESCO used the term “cultural cleansing” when describing and condemning the devastating destruction of the archaeological site at Nimrud, the ancient Assyrian capital. UNSECO continues efforts to mobilize the people of Iraq and the international political and academic communities to further protect cultural heritage sites in Iraq.

A final key historical topic that is still greatly debated today is the rightful ownership to the Elgin Marbles. The Elgin Marbles happen to be a large portion of the Parthenon frieze. The Elgin Marbles were removed from the Parthenon during the reign of the Ottomans over Greece by an Englishman by the name of Lord Elgin, for which the marbles are currently named. The Elgin Marbles have been held by the British Museum since 1816. Lord Elgin’s reasoning for removing the marbles were the state of deterioration as monuments were not being properly cared for at the time. While the Ottoman Empire spanned Greece, their ruling political government at the time of the sale of the Elgin Marble did not have any personal stake in the removal of the ancient artifact. Since Greece gained independence from the Ottoman oppression, the country was petitioned for the return of their artifacts they consider to be stolen.

The argument for repatriation of the Elgin Marbles in an article by Michael Kimmelman introduces an excellent example of encyclopedic museums overstepping their boundaries to inappropriately keep possession of ancient artifacts. Kimmelman documents the opening of the Acropolis Museum in Athens, Greece, a state-of-the-art encyclopedic museum with outstanding capabilities to both preserve and display ancient artifacts of their culture. Designed by Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, the Acropolis Museum sits near the base of the Acropolis. The museum houses the rest of the Parthenon frieze that Lord Elgin did not take, making do with plaster casts of the missing Elgin Marbles that complete the frieze. The displeasure of the missing Elgin Marbles is a national argument in Greece, with even the President of Greece affirming that the ancient artifacts were in fact stolen, and he offers his own support in his nation’s campaigning for the return of the Elgin Marbles to the rightful place.

According to UNESCO, who has been involved by initiation deliberations between Athens, Greece and the British Museum, their mediation and questions have gone unanswered by the British Museum. Since the 2009 construction of the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum in Athens, Greece, the British Museum’s long-standing claims of inadequate preservation and protection have been answered in full. Considering that the Elgin Marbles acquirer, Lord Elgin, was ambassador to a ruling empire that was not only oppressive but no longer rules, the British Museum’s argument for their ownership to the Elgin Marbles goes unfounded. The Ottoman Empire had no stake in ancient Greek artifacts, as they were an oppressive foreign government with no historical connection to the removed artifacts. the Elgin Marbles were not truly their possessions to sell to Lord Elgin and England. The act of taking the Parthenon frieze in 1816 while the country of Greece was under the rule of an oppressive regime was an issue of the past for which the British Museum is not fully held accountable; however, the refusal to return the Elgin Marbles to their rightful owners and original location shows a lack of ethics within the British Museum that Kimmelman feels greatly tarnishes the museum’s reputation in both academia and the general public.

Of all seven of the key topics discussed, it can be determined that the general purpose of our encyclopedic museums are to benefit mankind and our cultural heritage and preserve these ancient artifacts or world heritage sites. While armed conflicts bring about extremely difficult circumstances, having key diplomatic organizations such as UNESCO oversee peaceful mediations in certain controversial or emergency situation could bring about positive change in the art historical and preservation communities and initiate progress within these ancient artifacts and sites. Where our cultural heritage can be preserved and protected, great care and sometimes ownership should be given in light of how the artifacts can be preserved. However, ownership where ethics are not solid and preservation is no longer a topic for opposition, the discussion for repatriation should be on the able. Every situation will be different, and having organizations such as UNESCO to mediate between individual situations are very necessary for any hopes of reaching peaceful resolutions.

Works Cited

“Assyria at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” In The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 58, 167- 169. Boston, MA: The American Schools of Oriental Research, 1995.

Douglas, John H. “Treasures of a Boy-King.” In Science News, Vol. 110, 396-397. Washington, D.C.: Society of Science and the Public, 1976.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Ashur”, accessed April 21, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/38385/Ashur.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Hatshepsut”, accessed April 19, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/256896/Hatshepsut.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Pyramids of Giza”, accessed April 20, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/234470/Pyramids-of-Giza.

Kimmelman, Michael. “Elgin Marble Argument in a New Light.” New York: The New York Times, June 2009.

Long, Chas. Chaille. “Send Back the Obelisk!” In The North American Review, Vol. 143, 410-413. Iowa: The University of Northern Iowa, 1886.

McNeil, Donald G. “The Code of Hammurabi.” In American Bar Association Journal, Vol. 53, 444-446. Washington, D.C.: American Bar Association, May 1967.

Teeter, Emily. “Museum Review: Hatshepsut and Her World.” In American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 110, 649-653. Long Island, NY: Archaeological Institute of America, 2006.